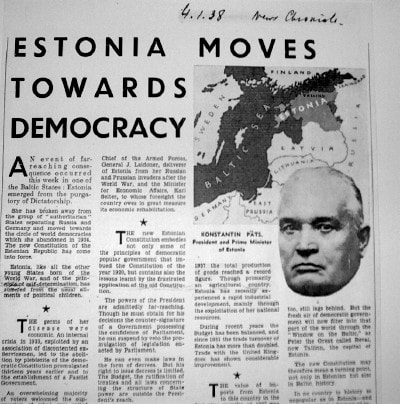

04.01.1938. Real dictator "president" Päts in foreign newspapers.

04.01.1938. Real dictator "president" Päts in foreign newspapers.

The Political Nature of the Union of Estonian Freedom Fighters – democratic or authoritarian Vaps Movement?

by Kristjan Valgur

The subject of this writing thesis is The Political Nature of the Central Union of Estonian Freedom Fighters – democratic or authoritarian Vaps Movement? And focuses on the question whether or not the Vaps Movement would have strived towards an authoritarian form of government with its political activities if they had obtained power.

The Vaps Movement grew out from the Union of Demobilized Soldiers, which united the veterans of the Estonian War of Independence that had ended a few years before. In 1923, Johan Pitka founded the Liberal National Party that aimed to fight against “corruption” and “national crimes”.

The party’s greatest success was 4 seats in the II composition of the Riigikogu and a short-term participation in the I government of Jaan Teemant. The Liberal National Party and the Union of Demobilized Soldiers can be considered as the predecessors of the Vaps Movement.

In 1926, as a successor to the Union of Demobilized Soldiers, the Union for Participants in the Estonian War of Independence was founded to whom several leading members of the Liberal National Party also joined, such as the famous retired admiral Johan Pitka. In 1928, generals Larka

and Põdder also joined the organization. In June 2 1929, the Central Union of Estonian Freedom Fighters was formed on the basis of the veteran unions in in Tallinn, Tapa and Haapsalu. On January 26 1930, the first congress of the CUEFF took place in order to discuss the issues of land and positions that had not been received from the state as promised and the economic hardships of the veterans.

On March 22 1932, the second congress of the CUEFF took place. By that time, the effects of the global economic crisis had already reached Estonia. Johan Pitka criticized the state’s corruptibility and its education policies. The lawyer Theodor Rõuk also spoke on the subject on the 1920 Constitution. The congress passed two resolutions: one on the creation of a presidential institution, the other on the reduction of the Riigikogu to 50 members. The third and fourth resolutions focused on stricter economic policies and the question of promised positions yet unresolved. The CUEFF began evolving from a lobby group to a political party.

Between the years 1931 and 1932, the freedom fighters started to be more actively involved in the constitutional debate. On June 26, the CUEFF submitted its memorandum to the Riigikogu on the subject of the constitution. As a result, the IV composition of the Riigikogu began working on its own constitutional draft.

The Riigikogu developed the Soots-Kuke draft which was accepted on the final hearing of the IV Riigikogu with 43 votes in favour and 30 against. Based on the constitutional draft of the IV Riigikogu, a 4-year term Riigikogu with 80 members would have been created and a presidential institution elected once every five years introduced. The president would have been significantly more independent from the Riigikogu and the government, but still needed the signature of the minister, whose field of expertise was involved, in order to enact a law. The referendum, taking place on August 13–15 1932, failed by a narrow margin of 50.8% votes against.

In 1932 the popularity and membership of the freedom fighters movement grew dramatically. The membership grew over 10 000 members and a weekly newspaper titled “Võitlus” was issued. On March 20 1932 the III congress of the freedom fighters summoned in order to discuss the old issues related to the veterans. But the actual topic was the state’s economic and political situation. The most important question discussed on the III congress became the enlargement of the organization’s membership. A new supporter member status was formed for people who had not participated in the Estonian War of Independence. Despite this, the CUEFF still kept its distance from larger politics.

The left side of the Estonian political arena began noticing the growing popularity of the freedom fighters movement. On November 27 1932, the IV congress of the CUEFF took place. A new charter and rules of procedure were introduced. Participation in political parties was banned for CUEFF members as well. After the IV congress, work on the new constitution began. At first, cooperation was made with the Riigikogu, but after IV congress, the organization begun forming its own draft which was presented to the Riigikogu on November 10 1932.

Rivalry arose between the Riigikogu and the CUEFF in the creation of the new constitution and putting it to vote. The Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs had rejected the CUEFF draft, but 56000 signatures were gathered as a result of a campaign, thus the new draft had to be put on a referendum. The V composition of the Riigikogu started the creation of its own constitutional draft in November 1932 and finished it by the end of December. In comparison to the previous draft, this gave more power to the Riigikogu.

With a change in the legislation on February 21, the Riigikogu decided to allow one referendum per year. The other decision reduced the necessary participation rate from 50% to 35%. The first on the vote was the Riigikogu’s constitutional draft. After the inauguration of Jaan Tõnisson’s IV government, the referendum of the Riigikogu’s second constitutional draft took place and failed like the one the year before. 161 595 votes were in favour and 333 107 against. The freedom fighters movement and socialist propaganda had been successful and the Riigikogu was forced to set a referendum for the freedom fighters draft on October 14–16, 1933.

The year 1933 brought along an escalation of the tensions in domestic politics. On June 1, before the referendum of the Riigikogu's second constitutional draft, Jaan Tõnisson decided to ban the activities of Tartu Union of Freedom Fighters within the Tartumaa county. In the same month, on the 27th of June, Tõnisson’s government devolved the Estonian kroon by 35%. This caused a wave of discontent among the population, although it helped towards Estonia’s economic recovery during the next few years.

The referendum for the freedom fighters constitutional draft was now inevitable for the Riigikogu parties. The political parties came to recognise the growing influence of the CUEFF in the Estonian society. The parties were split on the question of the new constitutional draft. After its own congress on June 18, the Joined Farmers’ Party decided to support the draft. The Farmers’ Councils (split on the matter), Rahvaerakond and the Estonian Democratic Socialist Workers’ Party were against the draft. On the 7th of August, the foreign minister Ants Piip proposed its own constitutional draft to the Riigikogu, but this did not go beyond its first hearing.

On August 11, 1933 Tõnisson declared a pan-Estonian state of martial law during which the CUEFF and the paramilitary units of several other parties were shut down. A decree was issued to limit the freedom of assembly and expression. With the decree of August 26, the media was subjected to censure.

Another blow that hampered the governments’ reputation after the delayed devaluation of the kroon was the scandal resulting from the sale of the warships “Wambola” and “Lennuk”, being a propaganda victory for the freedom fighters that was well exploited during the subsequent election campaigns. As a result, the popularity of the Riigikogu and the government fell to its absolute low.

On September 10, the freedom fighters started a campaign in support of their constitutional draft. Hundreds of meetings were held, leaflets distributed and articles published in the “Võitlus”. The campaign received considerable success.

Prior the referendum on the freedom fighters constitutional draft, the Riigikogu decided to raise the participation quota back to 50%. The motion was supported by 32 members of the Riigikogu. If the constitutional draft failed, the freedom fighters wished to continue in politics with legislative proposals and participation in the parliamentary elections. During the referendum held on October 14–16, the freedom fighters proposal gained 416 879 votes in favour and 156 894 votes against. The participation quota was surpassed with the result of 56%. After the proposal passed the referendum, there occurred a four-day long change in government, succeeded by the V government of Päts.

On October 28, the freedom fighters union, so far operating in isolated groups, was reformed under the name of Estonian Union of Freedom Fighers (EUFF). The temporary management comprised of Larka, Sirk, Seimann, Klaasmann, Jalakas and Telg.

The membership of the EUFF was comprised of active, supporter and honorary members. Its highest body was the congress and central management. Technical and day-to-day questions were dealt by the central headquarters. The central management held rank over county congresses which elected the county management. The smallest body of the EUFF was a section which required at least 8 members. On a local level, communication between sections was the responsibility of parish and village leaders. In addition, the movement had separate sections for women and specific trades as well as disciplinary units (characteristically of the parties at the time). So the movement was organized democratically with a centralized leadership in Tallinn, but without a leader principle (Führerptinzip) that many authors claim to exist.

On November 12, an extraordinary congress took place in Võru, where details related to the movement were discussed. Only members of the temporary central management and representatives of some larger towns were present. Andres Larka was elected as the candidate for the riigivanem position. Rules of procedure were passed and the positions of a campaign leader and the headquarters created. The details of the VI congress taking place on December 17 were also set. In November, the party started negotiations with the Joined Farmers to set a joint candidate of Johan Laidoner. There was also a failed attempt to cooperate with Päts. Johannes Zimmermann, representing the Joined Farmers, and Artur Sirk from the freedom fighters part managed to convince Johan Laidoner to run for the elections. Both parties promised to declare this on their congresses. The freedom fighters broke this promise a day before the VI congress took place.

At the same time there was a scandal growing among freedom fighters in regards to the purchase of a rotation printing machine from Germany. The socialist media pressed the issue and accused the freedom fighters of having ties with the national socialists, even though no proof existed to these allegations. Another source for concern was the endorsements of Viktor von zur Mühlen, leader of the local nazified Baltic-German party, and von Maydell, vice-leader of the Tallinn German Club, of the freedom fighters movement. The EUFF management condemned this on December 3, 1933.

On September 7, the organization proposed the Riigikogu a legislation titled “The law on the fight against Marxism”, which aimed to ban local left-wing parties. The Riigikogu declared the law as unconstitutional and the proposition had a negative impact on the freedom fighters reputation in the society.

On December 17, 1933 the VI freedom fighters congress was held in the Estonia theatre house. 1019 representative and 350 guests were present. The congress was opened by a speech from Sirk, who harshly attacked other parties in Estonia. Theodor Rõuk spoke on the subject of the new constitution. A new central management was elected for the movement: Artur Sirk, Aleksander Seimann, Theodor Rõuk, Eduard Kubbo, Oskar Luiga, Karl Podrästik, Johannes Holland, August Klaasmann, Paul Telg, August Kook, Karl Jalakas and Leonhard Laast-Laas. Andres Larka was elected as the chairman of EUFF and Sirk as vice-chairman. The EUFF participation in the municipal elections and the parliamentary elections was also declared. Andres Larka became the official riigivanem’s candidate of the freedom fighters.

The year 1934 started successfully for the freedom fighters. On January 7–8, local parish elections took place and borough and town elections on January 15–16. The freedom fighters were successful in bigger cities such as Tallinn, Tartu, Viljandi and Narva. In Tallinn and Tartu they achieved a majority. In rural regions, the freedom fighters did not manage to set their candidacy everywhere, thus the EUFF results in rural regions were meagre, only 8.9% of total votes. The main promise was fighting against “rampant corruption” and dealing with the unemployment problem.

On January 24, the new constitution came to effect. For the freedom fighters, this was a day for celebration. The EUFF also began preparing for the parliamentary and the presidential elections. On December 2, the committee responsible for the election of the riigivanem and the VI composition of the Riigikogu declared the elections, which were supposed to take place on April 22–23 and on April 29–30 respectively. Nomination of candidates took place on 23, 25, 26 and 27th February. On February 9–10 there were courses for rally speakers where instructions were given for the coming campaign. A fierce election campaign for the riigivanem position would begin, during which the freedom fighters aggressively assaulted their main competitor, Johan Laidoner. Political enemies responded in kind, criticising Larka’s poor health and supposed manipulation with his rank from the time of the War of Independence.

On March 5–21, a gathering of signature, obligatory to nominate a candidate for riigivanem, took place. It was necessary to gather at least 10 000 signatures. This was fulfilled within a single day, on March 5 which happened to be general Larka’s 55th birthday. The final result was about 65 000 signatures.

In February, the freedom fighters started receiving reports from the officials in the political police about a future shutdown of the organisation, lists of future arrests were already made. Warnings nature were also made by socialists in their rallies and in the media. It is not exactly known, when Päts and Laidoner reached an agreement on taking “preventive steps.”

In the beginning of March, Riigikogu took to hearing several bills, which forbade members of the army and state officials to participate in politics. This considerably reduced the potential support base of the freedom fighters.

On March 8, the EUFF sent a newsletter to its branches across the country, warning on the possible shutdown ahead. Member lists and documentations were destroyed and symbolic flags hidden. Last speeches took place on March 11. On March 12, the Päts-Laidoner coup took place in Tallinn, and the country was declared to be in a state of defence. The result was the closure of 400 freedom fighters’ sections. 500 members of the EUFF were arrested, although 425 of these were soon released from captivity. In his speech on March 15, Konstantin Päts confessed the existence of “a sickness of the Estonian people that needs to be cured.” The people initially supported the closure of the Estonian Union of Freedom Fighters, but during the next six months, it became apparent that Estonia had reached a “silent era.” Based on Roger Griffin's comparative model of general fascism, the EUFF was not a real fascist movement. The EUFF had some negations common with the ideologically 'pure' fascist movements, but lacks some of the radical elements: anti-conservatism and fascist 'socialism'. On the other hand the EUFF coincides with some of the negations, for example with anti-liberalism and the heterogeneity of fascism's social support. In conclusion, the EUFF could be considered a right-wing conservative movement.

The question, what would have become of the freedom fighters if democracy had prevailed in Estonia and the EUFF gained access to power, remains unanswered. There is no single answer. Most likely they would have won the riigivanem elections and received a moderate amount of seats in the Riigikogu elections. After the end of the economic crisis and the resolution of the political conflict in the society, the EUFF would have turned into a more moderate right-wing conservative party. The BA thesis concludes that the Union of Estonian Freedom Fighters was a democratic movement with a tendency towards authoritarianism.

Source / Allikas

by Kristjan Valgur

The subject of this writing thesis is The Political Nature of the Central Union of Estonian Freedom Fighters – democratic or authoritarian Vaps Movement? And focuses on the question whether or not the Vaps Movement would have strived towards an authoritarian form of government with its political activities if they had obtained power.

The Vaps Movement grew out from the Union of Demobilized Soldiers, which united the veterans of the Estonian War of Independence that had ended a few years before. In 1923, Johan Pitka founded the Liberal National Party that aimed to fight against “corruption” and “national crimes”.

The party’s greatest success was 4 seats in the II composition of the Riigikogu and a short-term participation in the I government of Jaan Teemant. The Liberal National Party and the Union of Demobilized Soldiers can be considered as the predecessors of the Vaps Movement.

In 1926, as a successor to the Union of Demobilized Soldiers, the Union for Participants in the Estonian War of Independence was founded to whom several leading members of the Liberal National Party also joined, such as the famous retired admiral Johan Pitka. In 1928, generals Larka

and Põdder also joined the organization. In June 2 1929, the Central Union of Estonian Freedom Fighters was formed on the basis of the veteran unions in in Tallinn, Tapa and Haapsalu. On January 26 1930, the first congress of the CUEFF took place in order to discuss the issues of land and positions that had not been received from the state as promised and the economic hardships of the veterans.

On March 22 1932, the second congress of the CUEFF took place. By that time, the effects of the global economic crisis had already reached Estonia. Johan Pitka criticized the state’s corruptibility and its education policies. The lawyer Theodor Rõuk also spoke on the subject on the 1920 Constitution. The congress passed two resolutions: one on the creation of a presidential institution, the other on the reduction of the Riigikogu to 50 members. The third and fourth resolutions focused on stricter economic policies and the question of promised positions yet unresolved. The CUEFF began evolving from a lobby group to a political party.

Between the years 1931 and 1932, the freedom fighters started to be more actively involved in the constitutional debate. On June 26, the CUEFF submitted its memorandum to the Riigikogu on the subject of the constitution. As a result, the IV composition of the Riigikogu began working on its own constitutional draft.

The Riigikogu developed the Soots-Kuke draft which was accepted on the final hearing of the IV Riigikogu with 43 votes in favour and 30 against. Based on the constitutional draft of the IV Riigikogu, a 4-year term Riigikogu with 80 members would have been created and a presidential institution elected once every five years introduced. The president would have been significantly more independent from the Riigikogu and the government, but still needed the signature of the minister, whose field of expertise was involved, in order to enact a law. The referendum, taking place on August 13–15 1932, failed by a narrow margin of 50.8% votes against.

In 1932 the popularity and membership of the freedom fighters movement grew dramatically. The membership grew over 10 000 members and a weekly newspaper titled “Võitlus” was issued. On March 20 1932 the III congress of the freedom fighters summoned in order to discuss the old issues related to the veterans. But the actual topic was the state’s economic and political situation. The most important question discussed on the III congress became the enlargement of the organization’s membership. A new supporter member status was formed for people who had not participated in the Estonian War of Independence. Despite this, the CUEFF still kept its distance from larger politics.

The left side of the Estonian political arena began noticing the growing popularity of the freedom fighters movement. On November 27 1932, the IV congress of the CUEFF took place. A new charter and rules of procedure were introduced. Participation in political parties was banned for CUEFF members as well. After the IV congress, work on the new constitution began. At first, cooperation was made with the Riigikogu, but after IV congress, the organization begun forming its own draft which was presented to the Riigikogu on November 10 1932.

Rivalry arose between the Riigikogu and the CUEFF in the creation of the new constitution and putting it to vote. The Ministry of Justice and Internal Affairs had rejected the CUEFF draft, but 56000 signatures were gathered as a result of a campaign, thus the new draft had to be put on a referendum. The V composition of the Riigikogu started the creation of its own constitutional draft in November 1932 and finished it by the end of December. In comparison to the previous draft, this gave more power to the Riigikogu.

With a change in the legislation on February 21, the Riigikogu decided to allow one referendum per year. The other decision reduced the necessary participation rate from 50% to 35%. The first on the vote was the Riigikogu’s constitutional draft. After the inauguration of Jaan Tõnisson’s IV government, the referendum of the Riigikogu’s second constitutional draft took place and failed like the one the year before. 161 595 votes were in favour and 333 107 against. The freedom fighters movement and socialist propaganda had been successful and the Riigikogu was forced to set a referendum for the freedom fighters draft on October 14–16, 1933.

The year 1933 brought along an escalation of the tensions in domestic politics. On June 1, before the referendum of the Riigikogu's second constitutional draft, Jaan Tõnisson decided to ban the activities of Tartu Union of Freedom Fighters within the Tartumaa county. In the same month, on the 27th of June, Tõnisson’s government devolved the Estonian kroon by 35%. This caused a wave of discontent among the population, although it helped towards Estonia’s economic recovery during the next few years.

The referendum for the freedom fighters constitutional draft was now inevitable for the Riigikogu parties. The political parties came to recognise the growing influence of the CUEFF in the Estonian society. The parties were split on the question of the new constitutional draft. After its own congress on June 18, the Joined Farmers’ Party decided to support the draft. The Farmers’ Councils (split on the matter), Rahvaerakond and the Estonian Democratic Socialist Workers’ Party were against the draft. On the 7th of August, the foreign minister Ants Piip proposed its own constitutional draft to the Riigikogu, but this did not go beyond its first hearing.

On August 11, 1933 Tõnisson declared a pan-Estonian state of martial law during which the CUEFF and the paramilitary units of several other parties were shut down. A decree was issued to limit the freedom of assembly and expression. With the decree of August 26, the media was subjected to censure.

Another blow that hampered the governments’ reputation after the delayed devaluation of the kroon was the scandal resulting from the sale of the warships “Wambola” and “Lennuk”, being a propaganda victory for the freedom fighters that was well exploited during the subsequent election campaigns. As a result, the popularity of the Riigikogu and the government fell to its absolute low.

On September 10, the freedom fighters started a campaign in support of their constitutional draft. Hundreds of meetings were held, leaflets distributed and articles published in the “Võitlus”. The campaign received considerable success.

Prior the referendum on the freedom fighters constitutional draft, the Riigikogu decided to raise the participation quota back to 50%. The motion was supported by 32 members of the Riigikogu. If the constitutional draft failed, the freedom fighters wished to continue in politics with legislative proposals and participation in the parliamentary elections. During the referendum held on October 14–16, the freedom fighters proposal gained 416 879 votes in favour and 156 894 votes against. The participation quota was surpassed with the result of 56%. After the proposal passed the referendum, there occurred a four-day long change in government, succeeded by the V government of Päts.

On October 28, the freedom fighters union, so far operating in isolated groups, was reformed under the name of Estonian Union of Freedom Fighers (EUFF). The temporary management comprised of Larka, Sirk, Seimann, Klaasmann, Jalakas and Telg.

The membership of the EUFF was comprised of active, supporter and honorary members. Its highest body was the congress and central management. Technical and day-to-day questions were dealt by the central headquarters. The central management held rank over county congresses which elected the county management. The smallest body of the EUFF was a section which required at least 8 members. On a local level, communication between sections was the responsibility of parish and village leaders. In addition, the movement had separate sections for women and specific trades as well as disciplinary units (characteristically of the parties at the time). So the movement was organized democratically with a centralized leadership in Tallinn, but without a leader principle (Führerptinzip) that many authors claim to exist.

On November 12, an extraordinary congress took place in Võru, where details related to the movement were discussed. Only members of the temporary central management and representatives of some larger towns were present. Andres Larka was elected as the candidate for the riigivanem position. Rules of procedure were passed and the positions of a campaign leader and the headquarters created. The details of the VI congress taking place on December 17 were also set. In November, the party started negotiations with the Joined Farmers to set a joint candidate of Johan Laidoner. There was also a failed attempt to cooperate with Päts. Johannes Zimmermann, representing the Joined Farmers, and Artur Sirk from the freedom fighters part managed to convince Johan Laidoner to run for the elections. Both parties promised to declare this on their congresses. The freedom fighters broke this promise a day before the VI congress took place.

At the same time there was a scandal growing among freedom fighters in regards to the purchase of a rotation printing machine from Germany. The socialist media pressed the issue and accused the freedom fighters of having ties with the national socialists, even though no proof existed to these allegations. Another source for concern was the endorsements of Viktor von zur Mühlen, leader of the local nazified Baltic-German party, and von Maydell, vice-leader of the Tallinn German Club, of the freedom fighters movement. The EUFF management condemned this on December 3, 1933.

On September 7, the organization proposed the Riigikogu a legislation titled “The law on the fight against Marxism”, which aimed to ban local left-wing parties. The Riigikogu declared the law as unconstitutional and the proposition had a negative impact on the freedom fighters reputation in the society.

On December 17, 1933 the VI freedom fighters congress was held in the Estonia theatre house. 1019 representative and 350 guests were present. The congress was opened by a speech from Sirk, who harshly attacked other parties in Estonia. Theodor Rõuk spoke on the subject of the new constitution. A new central management was elected for the movement: Artur Sirk, Aleksander Seimann, Theodor Rõuk, Eduard Kubbo, Oskar Luiga, Karl Podrästik, Johannes Holland, August Klaasmann, Paul Telg, August Kook, Karl Jalakas and Leonhard Laast-Laas. Andres Larka was elected as the chairman of EUFF and Sirk as vice-chairman. The EUFF participation in the municipal elections and the parliamentary elections was also declared. Andres Larka became the official riigivanem’s candidate of the freedom fighters.

The year 1934 started successfully for the freedom fighters. On January 7–8, local parish elections took place and borough and town elections on January 15–16. The freedom fighters were successful in bigger cities such as Tallinn, Tartu, Viljandi and Narva. In Tallinn and Tartu they achieved a majority. In rural regions, the freedom fighters did not manage to set their candidacy everywhere, thus the EUFF results in rural regions were meagre, only 8.9% of total votes. The main promise was fighting against “rampant corruption” and dealing with the unemployment problem.

On January 24, the new constitution came to effect. For the freedom fighters, this was a day for celebration. The EUFF also began preparing for the parliamentary and the presidential elections. On December 2, the committee responsible for the election of the riigivanem and the VI composition of the Riigikogu declared the elections, which were supposed to take place on April 22–23 and on April 29–30 respectively. Nomination of candidates took place on 23, 25, 26 and 27th February. On February 9–10 there were courses for rally speakers where instructions were given for the coming campaign. A fierce election campaign for the riigivanem position would begin, during which the freedom fighters aggressively assaulted their main competitor, Johan Laidoner. Political enemies responded in kind, criticising Larka’s poor health and supposed manipulation with his rank from the time of the War of Independence.

On March 5–21, a gathering of signature, obligatory to nominate a candidate for riigivanem, took place. It was necessary to gather at least 10 000 signatures. This was fulfilled within a single day, on March 5 which happened to be general Larka’s 55th birthday. The final result was about 65 000 signatures.

In February, the freedom fighters started receiving reports from the officials in the political police about a future shutdown of the organisation, lists of future arrests were already made. Warnings nature were also made by socialists in their rallies and in the media. It is not exactly known, when Päts and Laidoner reached an agreement on taking “preventive steps.”

In the beginning of March, Riigikogu took to hearing several bills, which forbade members of the army and state officials to participate in politics. This considerably reduced the potential support base of the freedom fighters.

On March 8, the EUFF sent a newsletter to its branches across the country, warning on the possible shutdown ahead. Member lists and documentations were destroyed and symbolic flags hidden. Last speeches took place on March 11. On March 12, the Päts-Laidoner coup took place in Tallinn, and the country was declared to be in a state of defence. The result was the closure of 400 freedom fighters’ sections. 500 members of the EUFF were arrested, although 425 of these were soon released from captivity. In his speech on March 15, Konstantin Päts confessed the existence of “a sickness of the Estonian people that needs to be cured.” The people initially supported the closure of the Estonian Union of Freedom Fighters, but during the next six months, it became apparent that Estonia had reached a “silent era.” Based on Roger Griffin's comparative model of general fascism, the EUFF was not a real fascist movement. The EUFF had some negations common with the ideologically 'pure' fascist movements, but lacks some of the radical elements: anti-conservatism and fascist 'socialism'. On the other hand the EUFF coincides with some of the negations, for example with anti-liberalism and the heterogeneity of fascism's social support. In conclusion, the EUFF could be considered a right-wing conservative movement.

The question, what would have become of the freedom fighters if democracy had prevailed in Estonia and the EUFF gained access to power, remains unanswered. There is no single answer. Most likely they would have won the riigivanem elections and received a moderate amount of seats in the Riigikogu elections. After the end of the economic crisis and the resolution of the political conflict in the society, the EUFF would have turned into a more moderate right-wing conservative party. The BA thesis concludes that the Union of Estonian Freedom Fighters was a democratic movement with a tendency towards authoritarianism.

Source / Allikas

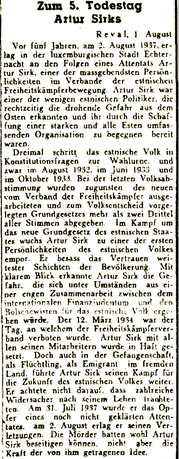

Revaler Zeitung, 2.VII.1942

Revaler Zeitung, 2.VII.1942

Versions of How Artur Sirk Perished

Authors: Jaak Valge, Art Juhanson

A letter written by the entrepreneur and public figure Oskar Rütli, who lived in Tartu, was made public over 60 years after his death. Rütli claims that Artur Sirk, the leader of the Estonian War of Independence veterans’ movement, was killed in the town of Ecternach, Luxembourg and describes how this happened.

This article is occasioned by Rütli’s letter to analyse the different versions of Artur Sirk’s death and to attempt to ascertain their validity. Two main versions are widespread: murder and suicide.

Neither version has been verified once and for all and summational analysis does not bring us any closer to the truth. The sources obtained from Luxembourg do not disprove or confirm suicide, and information hitherto disclosed by other researchers, for instance the writings of Villem Saarsen, are not convincing. The fact that the file on Artur Sirk has gone missing from the Luxembourg National Archives is a surprising circumstance that provides grounds for new suspicions. On the other hand, what is hitherto known also does not provide support for the murder version. The letter from Oskar Rütli, which contains several errors, also does not help in any significant way. Unfortunately, he has also left the source of his knowledge undisclosed. The primary research on the murder version has been conducted by Jüri Remmelgas. Numerous publications have been published on this theme but the evidence brought forth in them is contradictory.

A third version has also been suggested, according to which Artur Sirk fell out of a window as he was attempting to escape in panic. A new argument in favour of this explanation is brought forth in this article, but this version is also nevertheless hypothetical. In light of the knowledge that has hitherto been at our disposal, there are no grounds for considering this version any more convincing than the preceding two versions.

Tuna 4, 2018

THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE VETERANS' LEAGUE AND RELIGION (Main article in Estonian)

by Risto Teinonen

SUMMARY

The Veterans of the War of Independence of Estonia established an organisation in 1929, the initial aim of which was to protect the veterans’ interest and to perpetuate the memory of the fighters for the independence of the homeland and of those fallen. The movement became politicized quite quickly and its membership started to grow considerably, once new members didn't have to be war veterans.

These veterans’ organisations, first named Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Keskliit (The Central Society of the Estonian War of Independence Veterans) and since the end of 1933 Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Liit (The Estonian Society of the Estonian War of Independence Veterans), are considered radical right-wing organisations. Despite this fact, it has not been proved that the Veterans would have had contact with the nazis in Germany or the fascists in Italy, as it has been concluded by PhD Andres Kasekamp in the monograph The Radical Right in interwar Estonia (Macmillan Press 2000). The veterans refused co-operation with local Baltic-German National Socialists. At the same time, there was close co-operation with the radical right wing of Finland.

The veterans’ organisation cannot be considered fascist or national socialist. It stressed strong opposition to the head of state, but did so without giving up democratic ideas. The main political debate was about fighting for their draft of the constitution, which they won.

In the interwar period, there were radical right movements almost in all European countries. Their ideologies as well as their attitudes to religion differed greatly. In our neighbour-country Latvia, the prevalent radical right organisation was in favour of the ancient Latvian pagan religion while our Northern neighbor’s Finnish radical right movement was closely tied to the Lutheran church. The goal of this thesis was to study how the Estonian Veterans’ Organisation regarded religion.

The first part of the thesis shortly describes the European radical right movement in the studied period and the history of the Estonian Veterans’ Organisation. The third chapter studies how the relationship to religion is reflected in the charters of the veterans’ organisations, newspapers, activities and to what extent the clergy participated in the veterans’ movement. Since the veterans’ organisation was closed as the result of the coup organized by the State Elder Päts in March 1934, then the last chapter analyses the refugee life of the leader of the veterans Artur Sirk and describes the destinies of the clergy veterans who stayed in Estonia.

It can be concluded, that the Estonian veterans’ relationship to religion was positive, but not close. There were many active clergy members among the members of the veterans’ organisation and usually the veterans’ event – organisation’s summer gatherings, conferences, etc. – started with a sermon. When the veterans’ draft of constitution was accepted, then gratitude sermons were held all around the country. Also, the leader of the movement was in close communication with theologians until 1937 when he was probably murdered. In their attitude towards religion, the Estonian radical right were therefore on a very similar path with their Finnish counterparts, rather than with their Latvian counterparts, although the cultural background of all three was very similar.

Source